All Hallows: Art Institute of Chicago and the Problem of Evil

|

| Detail from Saint George and the Dragon, Bernat Martorell (1435) |

The Art Institute of Chicago may be best known for its curations of architectural details, its arms and armaments, and, of course, the magnificent Un dimanche après-midi à l'île de la Grande Jatte by George Seurat. You are not ready for the pointillist masterpiece until you're standing in front of it, close enough to inspect each colored point. Then backstep briskly and try to get all 7' x 10' of it in one view, then scan from side to side to take in the elegant ladies, reposing flaneurs and scampering children as they enjoy a quiet Sunday with each other, their dogs and at least one monkey. Seurat's was probably the first impressionist work I ever learned about, entirely due to the short Charley and Humphrey puppet segments that used to run between cartoons in the 1970s on KTVU channel 2: "Seurat knew a lot about the dot. And now so do you!"

But the AIC curates its share of creepers, as well. At the time of this writing, they are hosting an Exhibition of "Ghosts and Demons in Japanese Prints." I won't get to see it (and it ends inexplicably two weeks before Halloween), but hopefully it complements some of their other holdings such as the statue of the three-eyed thunderbolt deity, Shukongojin.

Two of the most visually stunning horrorshow pieces in their permanent collection are Mantorell's "Saint George and the Dragon" (1435), and Albright's (literal and figurative) "Picture of Dorian Gray" (1944). Both, of course, have their own European connections and some troubling aspects with how they represent evil.

Mantorell's dragon resembles a "greatest hits" approach to chimerical beasts, with an octopus tentacle for a tail, bat wings and a bizarre fish hook on the end of its doggish face. George seems to be having an easy day of the fight, with a calm, even serene expression as he readies to dispatch his foe. His horse seems a bit spooked, though.

In all of the representations of Saint George that I've seen around Europe, the dragon is rendered in less than formidable scale. In some cases, it seems to be little more than a lizard--certainly nothing requiring the intervention of a knight or sacred warrior. This also seems true of works showing the archangel Michael defeating Satan. In renaissance and medieval depictions, Michael is usually armored and bearing a sword or spear, while the fallen angel is naked or helpless, sometimes both. I suspect that the artists were commissioned to convey that even the most horrible beast is nothing in comparison to the defenders of the faith. But a great villain should have at least a little grandeur, if only to enhance the glory of victory. In the Old Testament, Goliath was a giant for a reason. Saint George putting down a collie-sized nuisance is one thing, but how much more glorious if the menace was Godzilla, or if Michael defeated Chernabog from Fantasia's Night on Bald Mountain?

The obscurity of evil in classic artworks contrasts with depictions of the punishments suffered by the damned--which were often quite explicit, with demons engaged in the sorts of raucous depravities that would later become attached to Christendom's more earthly enemies. In this way, Albight's unambiguous masterwork provides a perfect counterpoint to Mantorell's confusing monstrosity.

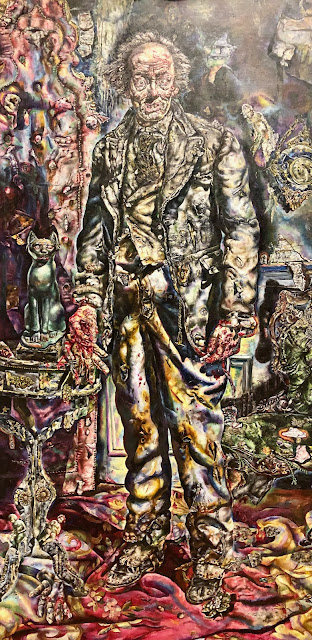

By the unanimous consensus of every knowledgeable art historian (in my imagination, anyway), Ivan Albright's greatest contribution was inspiring a touch of the grotesque to EC Comics and Mad Magazine artists such as Basil Wolverton, Graham Ingels, and Will Elder. This inspiration came in no small part from his commission to create the painting of Dorian Gray in his final, corrupted form for the 1945 film based on Oscar Wilde's 1891 novel. The movie is entirely in black and white except for the painting's revelation of what Dorian's years of debauchery had wrought upon his soul. While the camera does not linger on Albright's picture, you see enough to understand how the Victorian mindset perceived sexual deviance and, worse still, French novels that influenced the same.

|

| The Picture of Dorian Gray, Ivan Albright (1944), © The Art Institute of Chicago. |

Wilde's French connection, of course, is that he spent his final, post-imprisonment years in Normandy, and is buried in Cimitière Père Lachaise in Paris. His grave remains one the most visited in the cemetery, along with the final repose of another expatriate "libertine," Jim Morrison, the least talented member of one of the baby boom's favorite rock bands.

Wilde also shares his European predecessors' tendency to obscure the evil that is so central to his artistic purpose. Reading the book (bored stiff all the while, but determined to give such a renowned horror classic a fair hearing), I couldn't shake the feeling that the "sensualism" that propelled Dorian towards callous indifference and murder amounted to not much more than than gay sex, booze and opium. Wilde never makes this clear, even though it is Dorian Gray's offstage actions that set in motion the corrosion of his painted soul. It's known from early drafts of the novella and from correspondence with Wilde's publishers that the ambiguity surrounding the debauchery in question had more to do with taming the story's explicitly homoerotic elements, rather than the author's desire to let each individual reader and each generation imprint its own taboos onto Dorian's behavior. Or maybe he meant that the real corrupting influence was refusing to internalize the pieties and social condemnation of private, consensual activities. Or overly internalizing them. Maybe. Let's at least agree that murder is bad.

Frankly the story is a muddled mess--but the absolute grotesqueness of Albright's painting clarifies things, some 50 years after the book's publication. Look at the painting. Even in the society that put Wilde himself on trial and in prison for degeneracy, would the author's actions rate the horror that Albright depicts as the corruption of a human soul? Dorian Gray is so rotted and repugnant that you could easily accept that he had crossed the line from run of the mill debauchery to the kind of outrages alleged at historical villains such Vlad Tepes, Gilles de Rais, and Elizabeth Bathory.

And this is the problem, because those crimes--including mass murder and cannibalism, notably of children--were basically retreads of the blood libel sort used to persecute Jews and heretics such as Cathars, and have been evoked in about every subsequent inquisition, pogrom and moral panic.

That's just Albright's interpretation, of course. But perhaps he was imply and astute reader. Wilde's book includes more than casual anti-semitism in its representation of a Jewish theater manager; long before Dorian's picture is finally revealed, we are given a concrete example what it means to be "hideous," "vile," monstrous and repellent. The historical allusions would have been crystal clear to Wilde's contemporary readers.

In this way Albright gives a glimpse of how uninhibited medieval and renaissance artists might have amplified the righteous feats of Saints George and Michael, without ever having to engage Christendom's monstrous excesses in numerous inquisitions, crusades and wars of religion: If you want to convey your horror of evil, make it really fucking horrible.

Comments

Post a Comment