All Hallows: Saint Denis Loses It

|

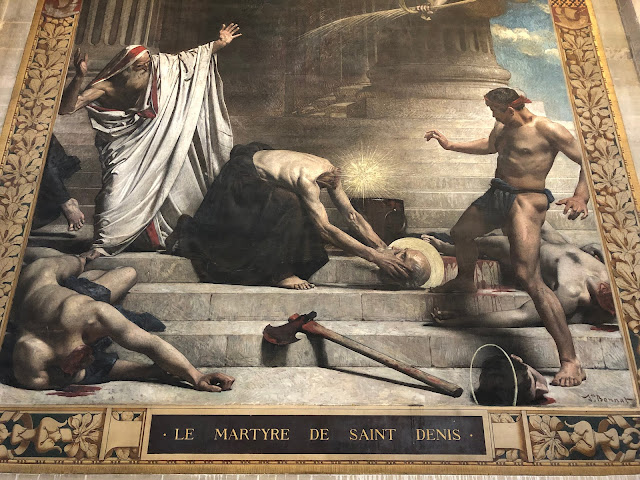

| "Le Martyre de Saint Denis" by Léon Bonnat (1880), Pantheon, 5th Arr. |

Saint-Denis was the first Bishop of Lutece (now Paris), sent by Pope Fabian to convert the Gauls to Christianity in the 3rd century BCE. His efforts apparently annoyed some of the local pagan clergy, who complained to the Roman governor, who was already dealing with an ambiguous edict from Emperor Decisus regarding the status of non-ancestral Roman deities. Maybe it was all just a big misunderstanding, but it resulted in Denis and two companions getting dragged up to the highest hill in town and beheaded. That hill is now named Montmartre, a portmanteau for "martyr's mountain."

What happened next must certainly have annoyed the original plaintiffs: Denis picked up his head, cradling it in his arms while preaching a sermon on his way back down the hill. The spot where he finished is now the site of Basilique Cathédrale de Saint-Denis.

|

| Saint-Denis, exterior of Cathédrale Notre-Dame, Reims |

Catholic martyrs are often represented by the manner in which they were killed--think of Saint Sebastian pierced with arrows, or Saint Bartholomew with his flayed skin draped over his arm like a cloak. Saint Denis is usually depicted carrying his head around. But Léon Bonnat's 1880 mural in the Pantheon shows the scene immediately after the execution, in the moment when the iconography is established. It is graphic and horrifying. Denis' companions, Rusticus and Eleutherius, are bleeding out from the neck. A severed head lies at the terrified executioner's feet. Denis lunges forward, head in hands and turned backwards to look at his own decapitated body.

Now, there is nothing funny whatsoever about sectarian or state violence. But it has to be admitted: as horrifying as it is, Bonnat's rendering of the scene also has comedic elements. You can imagine the executioner and the pagan priest screaming pell-mell down the hill, terrified that the seemingly immortal Denis will pick up the bloodied axe and take his vengeance. They don't know how the story ends, but we do. That frees the (modern, cartoon-savvy) viewer to imagine dust clouds streaming in their wake while Denis blinks in wonder before shrugging and continuing his sermon. That's All Folks!

In its combination of horror and comedy, Bonnat's mural reads as a satire, with the artist thumbing his nose at arbitrary power over life and death and the futility of trying to repress ideas out of existence. I don't know that this was his intent. After all, Bonnat was a member of the Ordre national de la Légion d'honneur and the Academie des beaux-arts. In France, that's about as Establishment as it gets, and neither the Second Empire (1853-1870) nor Third Republic (1870-1940) governments of Bonnat's lifetime would have had much interest in elevating smart-ass free-thinkers to positions of great prestige.

So who knows.

The beautiful part is that for all their talent and effort, artists don't get the last word on how their work is interpreted. For me, Bonnat's Saint-Denis sits comfortably with literary horror-comedy satires such as Poe's 1841 "Never Bet The Devil Your Head" (skewering transcendentalism) and HH Munro's 1911 "The Open Window" (Edwardian gentry life)--but better still with films such as Return of the Living Dead (military secrecy), Get Out (racism), Ready Or Not (the inhumanity of the super-rich), and Cabin in the Woods (the stifling conventions of horror films). It's a nice example of using horror and graphic violence to communicate what they see as a social menace and intentionally adding relentless humor to ridicule and undermine it.

The targets may not be equally important--I still sleep well despite the lingering scourge of transcendentalism--and the combination of horror and humor may not be well balanced. But in the horror genre, at least the satirist has a point of view beyond trying to manipulate the audience with gross-outs and jump scares.

Within the genre of beheading art, Bonnat can't hold a candle to Artemisia Gentileschi.

ReplyDelete