Ways of Remembrance

|

| Place Salvador Allende, 7th Arr. |

The Mairie de Paris (city hall) placed wreaths outside the Chilean embassy to commemorate 50th anniversary of the assassination of President Salvador Allende during the U.S.-backed coup of September 11, 1973.

There are memorials and commemorations all over France for people who died in war or through acts of political violence--fitting, for a place whose history was one of pretty much continuous warfare until the end of the Algerian war in 1962. In Paris and in some smaller places, just about every parish and mairie has a large, prominent war memorial, many that list the names of local residents or parishioners who died at war.

|

| A partial list of the war deceased of the parish of Sainte-Clotilde, 7th, Arr., which also honors parishioners killed in WWII. |

This personalization of the dead seems to have started in WWI, and occurs less consistently for casualties of WWII and later wars such as Indochina or Algeria. And except for fallen military leaders and nobility, you will never see the names of those who died in earlier battles fought during (for example) the Hundred Years' War, the Thirty Years' War, the Napoleonic wars or the Franco-Prussian War.

Perhaps the scale of death and destruction during WWI--and the dream that common soldiers and civilians died for the cause of "ending all wars"--prompted the memorialization of common soldiers. Modern record-keeping may also facilitate personal memorialization. For example, the Ministry of Defense maintains a searchable website for those who had "mort pour la France" (died for France)" beginning with casualties of WWI when the designation was adopted for the purposes of awarding survivors' pensions.

And critically, in WWII, "mort pour la France" was awarded to combatants who died in service to the resistance or Free France--not for the Petain government. But the Catholic church is nothing if not a superb records repository--with births, baptisms, marriages, and deaths recorded for centuries. Certainly the parish memorials could include names from the "pre-modern" era. Instead, the common soldier and civilian casualties who died for France's monarchies, empires, and republics remain largely anonymous and forgotten in the public sphere.

Some memorials are very personalized. All throughout Paris, affixed to the walls of buildings and quays, are simple concrete plaques marking the spots where individual fighters were killed during the Liberation of Paris from August 19-25, 1944. These plaques are also affixed to the residences of persons who were killed by German occupation forces or Vichy authorities, or who died during deportation to death camps.

|

| "Died for France, Henri Jean Pilot, law student, fell heroically at age 23, 20 August 1944, for the liberation of Paris." Affixed just outside the Assemblée Nationale, 7th Arr. |

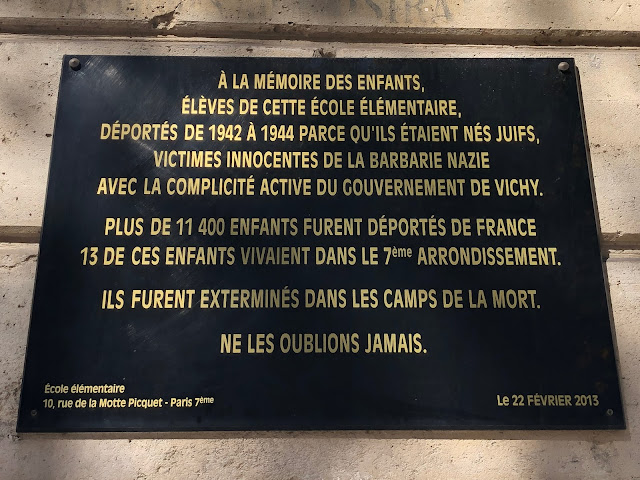

The most poignant of the "small" memorials list no names at all. Instead they are affixed to the walls of schools and note the numbers of students--predominantly Jews--who were rounded up by the Gestapo, deported to camps, and killed. Importantly, these memorials almost always call out the complicity of French authorities. It's that last touch--national accountability--that lends meaning to the admonition that we must never forget what authorities do in the name of the nation: "Ne les oublions jamais."

Comments

Post a Comment